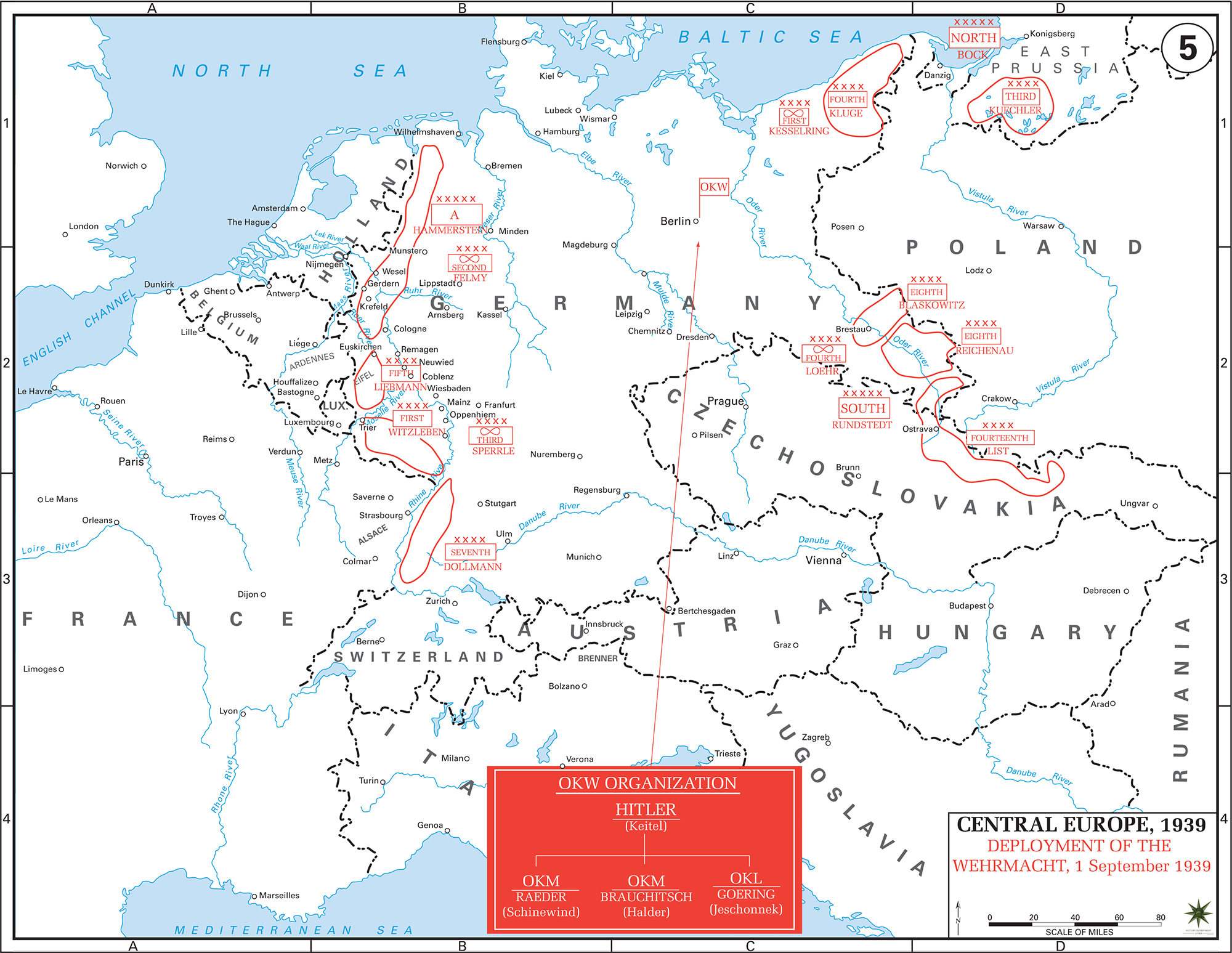

Map Description

History Map of WWII: Central Europe 1939 - Wehrmacht

Illustrating:

Deployment of the Wehrmacht, September 1, 1939

The German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, marked the beginning of World War II in Europe.

This military operation, codenamed Fall Weiss (Case White), had been meticulously planned months in advance, with

Hitler ordering the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) to develop operational plans as early as April 3, 1939.

Planning had informal roots even as early as late 1938, following the Munich Agreement and

German occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

When Mussolini informed him on August 25, 1939, that Italy was not prepared for war and would be unable to fulfill

its alliance obligations without massive material support, Hitler temporarily postponed the attack, originally

scheduled for August 26. However, he quickly reversed course and ordered the invasion to proceed on September 1.

This decision came despite the formal military commitments binding both France and Britain to defend Poland — specifically,

the Anglo-Polish Mutual Assistance Pact signed on August 25 and the longstanding Franco-Polish alliance — effectively

ensuring that a German attack on Poland would trigger a broader European conflict.

The Wehrmacht's deployment for the invasion of Poland was not a hasty maneuver but the result of months of

detailed preparation. Operational planning for Fall Weiss had begun by early April 1939 and was substantially

complete well before the announcement of the Nazi-Soviet Pact on August 23. While the pact is often portrayed as

the key enabler of the invasion, it primarily served to secure Germany's eastern flank by ensuring Soviet

non-intervention—and, through a secret protocol, Soviet cooperation in the partition of Poland. Though the invasion

was militarily feasible without the pact, its political and strategic assurances significantly strengthened

Hitler’s resolve to proceed.

:: Force Distribution and Military Operations ::

All in all, for the invasion of Poland, the total German invasion force was about 1.5 million troops,

divided between two army groups (Heeresgruppen). These were:

Heeresgruppe Nord (Army Group North), and

Heeresgruppe Süd (Army Group South)

In the west, Germany had

deployed a minimal but sufficient force to maintain a basic defensive posture along the French border. While

this allocation was far from robust—consisting of roughly ten divisions, many understrength or inadequately

equipped—it was deemed adequate given the anticipated caution of the French high command. This strategic risk

allowed Germany to concentrate the bulk of its offensive strength against Poland, gambling that France would

not launch a major offensive during the critical early weeks of the campaign.

The campaign was characterized by both ground and air assaults, with cities like Warsaw and Brześć nad Bugiem (Brest)

becoming targets of air raids.

:: The German Wehrmacht ::

What does the term “Wehrmacht” refer to in Nazi Germany?

The entire German military, including army, navy, and air force.

"Wehrmacht" means "defense force" in German and refers collectively to the Heer (Army), Kriegsmarine (Navy), and Luftwaffe

(Air Force) from 1935 to 1945. It does not include the SS, which was a separate organization.

The German Wehrmacht replaced the Reichswehr in 1935. On March 16, 1935, conscription was reinstated, violating the Treaty of Versailles.

Quick note on the SS:

Not a part of the Wehrmacht, the SS (Schutzstaffel) was originally founded in 1925 as Adolf Hitler’s personal bodyguard

unit, but it grew into one of the

most powerful and feared organizations in Nazi Germany.

By WWII, the SS had two main branches:

Allgemeine SS (General SS) – handled policing, intelligence, and racial policy enforcement.

Waffen-SS (Armed SS) – an elite military force that fought alongside the Wehrmacht but was separate from it.

The SS was led by Heinrich Himmler and played a central role in enforcing Nazi ideology, especially the Holocaust,

running concentration and extermination camps through the SS-Totenkopfverbände.

Unlike the Wehrmacht, the SS was ideologically driven, with strict racial and political selection criteria. It was

declared a criminal organization after the war due to its direct involvement in war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Back to the Wehrmacht:

OKW Organization and Key Military Leaders

The Wehrmacht's command structure during the Polish campaign was organized as follows:

OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) - The High Command of the Armed Forces was headed by Hitler himself as Supreme Commander,

with Wilhelm Keitel serving as Chief of the OKW. Keitel essentially functioned as Hitler's military chief of staff,

executing the Führer's directives across all branches of the armed forces.

OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres) - The Army High Command was led by Walther von Brauchitsch as Commander-in-Chief, with

Franz Halder serving as Chief of the General Staff. They were responsible for the ground operations that formed the

backbone of the Polish campaign.

OKM (Oberkommando der Marine) - The Navy High Command was headed by Grand Admiral Erich Raeder as Commander-in-Chief,

with Otto Schniewind serving as Chief of Naval Staff. While the navy played a supporting role in the Polish campaign,

it was responsible for naval blockades and securing maritime approaches.

OKL (Oberkommando der Luftwaffe) - The Air Force High Command was led by Hermann Göring as Commander-in-Chief, with

Hans Jeschonnek as Chief of the General Staff. The Luftwaffe played a crucial role in the campaign, conducting bombing

raids on Polish cities and providing tactical air support to ground forces.

:: No Micro-Management ::

Auftragstaktik (literally "mission tactics") is a German military command doctrine that emphasizes

decentralized decision-making, subordinate initiative, and operational flexibility. Rather than dictating each step,

commanders convey their intent and overall objectives, leaving the precise method of execution to subordinates on the ground.

The roots of Auftragstaktik reach back to the early 19th-century Prussian military reforms initiated by Gerhard von

Scharnhorst and August von Gneisenau. In the wake of Prussia’s defeat by Napoleon, these reformers overhauled the

military by promoting merit over privilege, improving officer education, and encouraging critical thinking—essential

preconditions for the later development of mission-based command.

The concept was further shaped by Carl von Clausewitz, whose seminal work On War analyzed the unpredictable nature of

combat, stressing the need for flexible leadership amid the “fog of war” and “friction.” But it was Helmuth von Moltke

the Elder, Chief of the Prussian General Staff from 1857 to 1888, who operationalized these ideas. Under his leadership,

Auftragstaktik became a guiding principle for Prussian officers. Moltke famously stated:

“No plan of operations extends with certainty beyond the first encounter with the enemy’s main strength.”

This philosophy empowered junior officers to adapt and act decisively without waiting for higher command, provided they

upheld the commander’s intent.

The doctrine continued to evolve, and its full institutionalization occurred under Hans von Seeckt, Chief of the Reichswehr

from 1919 to 1926. Confronted with the Versailles Treaty’s limitations on Germany’s armed forces, Seeckt focused on quality

over quantity. He codified Auftragstaktik into training manuals, emphasized intellectual rigor in officer education, and

instilled a command culture based on trust, autonomy, and adaptability. His reforms ensured that the doctrine was not

merely a tradition but a core operational principle of the interwar Reichswehr and later the Wehrmacht.

Though not the originator, Seeckt is credited with transforming Auftragstaktik from a theoretical and cultural tradition

into a formalized, modern command philosophy. This doctrine contributed significantly to the German military’s agility and

effectiveness during World War II and has since influenced contemporary military practices worldwide, including in NATO

forces.

Back to the invasion of Poland:

:: Consequences of the Invasion ::

The invasion had devastating consequences for Poland. Warsaw surrendered on September 28, 1939, following intense

aerial and artillery bombardment, and after the Polish government had evacuated the capital. Civilian casualties

in the city are estimated at around 20,000 to 25,000 killed, with total casualties—including wounded—approaching 50,000.

Approximately one-quarter of Warsaw’s buildings were destroyed during the siege.

The campaign concluded by October 5, 1939, with Poland effectively defeated. The Soviet invasion on September 17, 1939,

further sealed Poland's fate.

Credits

Courtesy of the United States Military Academy Department of History.

Related Links

About World War 2WWII Timelines